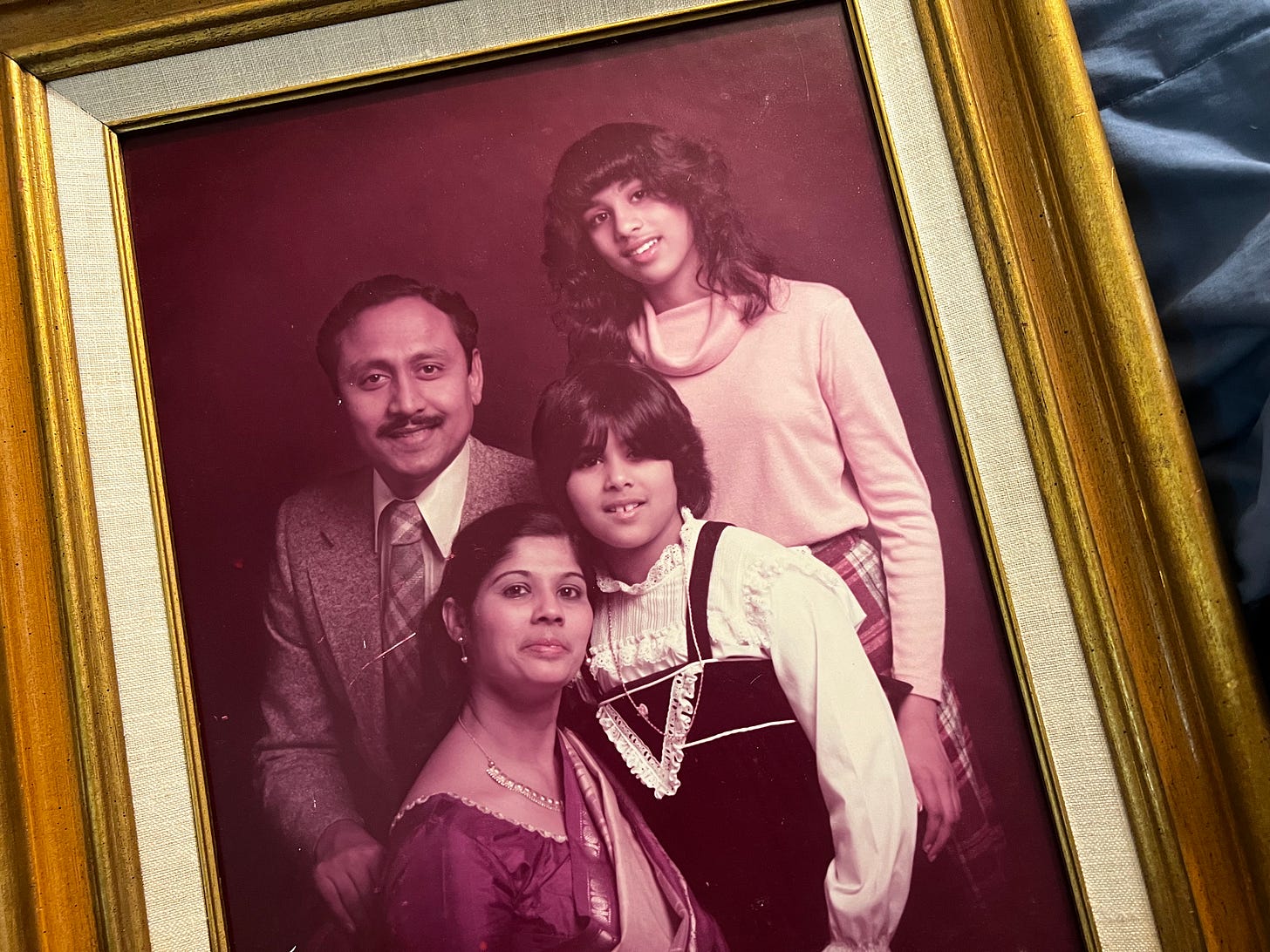

It was a Saturday in late March 2004, our boy’s first birthday, eleven months and one week after we’d brought him home from the adoption agency. Somehow nineteen people were seated in our narrow rowhouse living room amid multicolored extruded plastic playthings and soft chewable animal facsimiles. Almost everyone was happy, chatting, and eating cake. Upon arriving early, my father was at first animated and playful with his grandson in his arms, singing him the “Kookaburra” song the same way he’d sung it to me and my sister long ago. I watched him with cautious contentment. But soon he and his wife Edna both grew aloof and planted themselves morosely in a corner. They must have felt out of place among Patrick’s many boisterous cousins, aunts, and uncles, who’d arrived fashionably late en masse from Queens and Long Island.

I suspect that my father’s hearing loss had become deeper and that he was feeling cut off and depressed because of it. Of course, he’d long been hiding some other nameless darkness under his charming self-presentation. I too had been suspended in a similar state of half-faked okayness for much of my life. But this era was different. My habitual extroversion was now matched by genuine internal joy. I no longer felt split in two. I had been able to keep a small person alive and thriving, while also going out a few times every month to play my first dozen…two dozen…forty professional music gigs among peers who’d been doing so all their lives, who welcomed me as if I’d always been in the same line of work. Spring 2003 to spring 2004, motherhood plus musicianship—a double triumph and powerful dose of self-healing.

There was a very popular parenting book that had warned against a big celebration for the typical one-year-old, who might be upset by all the hubbub and attention. But our boy was an outlier, a born people-person. He had been smiling socially since the age of six weeks, laughing out loud and with so much personality at a time when other babies were still basically meatloaf. And now he was completely at ease as he was passed around the room from aunt to uncle to second cousin and back.

In my mother’s lap, however, things changed. She clasped the baby awkwardly in the circle of her arm. His little arms were pinned and his butt was slipping sideways off her lap. He looked mildly bewildered and on the verge of tears. Watching him squirm in my mother’s grasp, it was as if I was actually inside his little body with him: I could feel myself shrinking from her touch. He knew. He could feel the depths of her unease or maybe the better word is dis-ease. The lack of safety within her. I swear I had not telegraphed a thing—I was on the opposite side of the room, busy cleaning up cake plates and refreshing people’s drinks. I did not have to tell this prodigiously intuitive little person that his grandmother possessed no solid adult center.

My mother’s voice was high and brassy as she issued odd little commands.

Smile, baby, smile! Smile for grandma!

This was a boy who would smile happily and readily even among complete strangers, but not for Grandma, at least not on cue.

Later, when he was watching his beloved Baby Mozart video, she ordered him to Dance, baby, come on, dance, dance! When he was on the floor with the rolling walker she’d bought for him: Walk! Walk!

Seeing one of Patrick’s uncles aiming a camera at her for a nice, relaxed, candid shot, my mother suddenly stood and picked up the baby in one arm while grabbing Patrick’s father to join her in the picture.

Patrick’s father, of all people!—a retired New York City cop, racist enough that he had told Pat two year earlier that we would be stupid to adopt a Black baby. He was now doing his best to act like a grandfather and to pretend our son’s existence in our lives didn’t bother him. Who knows what he really thought or felt, and who cares? The man would end up drinking himself to death before too long. Other than the fact that he left a small insurance policy to his one other grandchild and nothing for our boy—a circumstance more likely due to alcoholic forgetfulness than outright hostility—we never had to witness how his attitude toward his African-American grandson would play out over time.

In any case, my mother grabbed a hold of Patrick’s father and turned what was supposed to be a candid shot into something awkward. Two adults who didn’t really know each other, both of them forcing smiles, while my son, with a deer-in-headlights look in his eyes, was nearly slipping from my mother’s grasp.

My own grandmother was also at the party, a shy, tiny, ancient presence, but still able to muster enough energy and strength to toss a big blue rubber ball back and forth across the living room carpet with the baby. Her own grand-maternal control-freak days were behind her, I presumed. (Sandhya!? Sandhya!? You brush your teeth, Sandhya? You sure? No, let me see. Let me see. Do it again, let me see.) All these decades later I didn’t have any reason to dislike the old woman, and yet a certain collusion among Jesus, the Gujarati language, and the family trait of incessant badgering had kept me distant. This was my matriarchal legacy, then. I did not really love my own grandmother, had to work hard just to tolerate my mother, and now my mother was the hard-to-love grandmother of my easy-to-love boy.

Meanwhile, my son and I were gaga for each other. We were thick as thieves, that baby and me. I could barely go fifteen minutes without wanting to kiss and hug him, although I was also careful about cultivating a necessary amount of detachment: not intervening as he tried and failed to pull himself up to standing; letting him bash on plastic or wood toys in frustration until he figured out on his own that the square peg needs to go in the square hole, and later on, letting him fall and cry in the playground so that he could learn for himself that the world wouldn’t end then, that mommy would kiss his boo-boo and soon he’d forget his worries. I deliberately practiced how to be fully present without over-identifying, hovering, or helicoptering. I was determined not to project fear and doubt onto his confident little being.

In those early days, I tried to put my own issues aside and play the intermediary between grandparents and grandchild. I wanted to give them all a chance, wanted not to poison my son’s relationship with his elders. I owed that to him if not to them. And my parents did okay playing their parts, up to a point.

Earlier that year, my mother and I had gone to the Babies-R-Us on Route 40 and she’d paid for a slew of clothes in many sizes to cover the next few years of growth. She was happier than I’d ever seen her. It was as if we were a normal mother-and-daughter adult team, out and about on a Saturday afternoon, but this was actually our first shopping trip together since I was a teenager. I had asked her once to take me to the Livingston Mall for a new swimsuit, and the micro-trauma of that afternoon was still imprinted in my memory twenty years later. I remember coming out of the dressing room upset about needing to go up a size, from a junior 7 to a junior 9—which was still, of course, perfectly reasonable for a girl of five-foot-six, especially back in the early 1980s when US sizes were all smaller than they are today. Rather than reassure me that I was simply growing broader and curvier in exactly the way I was supposed to grow—because that was the plain truth of the matter—my mother dismissed me with this helpful advice:

Well, just stop getting fatter, then.

As our boy grew older he would actively seek out connection with his grandparents: he would clamber into laps to ask questions, lots and lots of questions. It made me wonder if he might want to grow up to be a writer or journalist one day. I had no intention of pushing any kind of career path on this child. That, at the very least, was one mistake I would not accidentally recapitulate.

Grandma, the boy once asked, have you ever met Grandpa?

He rarely saw them in the same room together and he didn’t understand that they had once been married the way his own mother and father were married.

Grandpa, did you play soccer like me when you were a boy in India?

Sometimes I wondered where he got it, his effortless attachment and engagement. Then I’d remind myself that this was normal, this easy and readily available love. This was how families felt about each other in the absence of complicating factors like chronic depression and pathological self-involvement.

What became baffling over the years was that neither of my parents put much time or attention into the relationship. Our child had only one truly engaged grandparent, Patrick’s mother, who lived in nearby Dover, Delaware, and made a point of visiting or inviting us over at least a few times a year. One was better than none, I hoped. She became my surrogate mother, as well: a stable and kind presence who’d done a good job raising her sons despite her unhappy marriage to Pat’s troubled and troublesome dad.

My father and Edna were by now settled in Durham, North Carolina. Several times a year they drove right past Baltimore—on a stretch of I-95 that you could literally see in the distance from our front door—to visit friends back in New Jersey, but rarely bothered to visit us en route. Sometimes I’d blame myself. I could still be cold and angry with my father. Maybe it was too much to ask him to weather my shifting moods. But then I’d remember that he’d always been a not-quite-there guy, even when we were living under the same roof. He’d always depended on women to do the emotional connecting for him, and once Edna had decided—to her credit—not to be his social secretary, it was almost guaranteed we’d never hear from him.

Birthdays and other special occasions had been problematic forever. Immediately post-divorce my parents liked to put on a show of pretend solidarity. Thanksgiving 1993 had taken place at my father’s townhouse in West Orange, but it was my mother who had cooked the entire meal, turkey and all the usual sides, plus a huge portion of chicken curry, at her house a few miles away. Then she had dressed up as if for a fancy party and brought everything over in large covered foil trays.

I tolerated all this in my unsmiling manner. For whom was this charade enacted? It presented itself as an act of parental love but felt like a continuation of a decades-long fraud. I suppose they meant it as a form of damage control. But for me the damage was ongoing. At the table were my parents, my sister, and my then-new boyfriend Patrick. Edna had been spirited off the scene, as had my mother’s paramour, Edward. (Weird but true: my father was with a woman named Edna and my mother was with a man named Edward, as if they’d gotten a two-for-one discount on post-divorce partners.)

My father raised his glass to make a toast.

We’re still together after everything. He looked hopefully around the table and smiled. It’s good.

I can’t explain why but I wanted to throw the carving knife at his head.

We ate in near-silence, as usual. My mother asked who made the fruit salad, all innocence in her voice—as if her question wasn’t a form of challenge. I’m sure she knew it was Edna. Her face was a mask of blush and face powder, and her eyes, behind her glasses, looked at no one and nothing. A friend, my father responded—as if his self-protective reticence was a form of respect.

In the middle of the night, in my father’s guest bedroom, I awoke suddenly, startled not by any external noise but by dark anxious clamoring from deep inside myself. Huge silent tears began dribbling out of my eyes before I was even fully conscious. I scurried down to the living room so I wouldn’t wake Patrick, and found my journal and a pen in my purse.

What is wrong with me? Why does this pain get worse every year instead of better?

The faux communal events with my family continued for many years, and yet my tearful pessimism circa 1993 had been shortsighted. Things changed, eventually. The pain lessened, bit by bit. I bottomed out and got the help I needed. I matured. I raised an ebullient, inquisitive, confident baby boy and I played a lot of music and I restored myself to myself. I estranged myself from my mother when it seemed a critical decision for the sake of my own wellness and my effectiveness as a parent. It’s not that I never went through dark moods anymore, but they were never as deep or long-lasting. I was no longer merely my parents’ child, I was first and foremost my son’s mother. Birthday after birthday he was proving himself to be a fundamentally joyful creature, and it strengthened my own capacities for lightness and heart. He and I were a feedback loop of love.

Once, when our boy was two or three years old and both my parents still lived in New Jersey, my father and Edna hosted a Christmas party at their West Orange townhouse and invited my mother. By this time everything was out in the open and these three adults acted as if they were friends, although Edward was never in attendance and was perhaps never even invited. I suspect that in the way of the patriarchal male, my father would not have tolerated Edward’s presence or vice versa. I never became close with Edna—we had nothing in common—but I suppose I was happy enough, or relieved, to see my father with someone who seemed relatively sane.

The dozen or so partygoers were mostly friends from the church Edna and my father now attended together. I think it may have been a Baptist congregation. My father’s religiosity was growing less Anglo-ecumenical and more fire-and-brimstone with each passing year. Scotch and soda flowed into the lowball glasses and Sinatra was on the stereo. Bowls of chips, nuts, and candies competed for table space among my father’s overabundant tchotchkes. A young Filipino-American woman leaped toward me with a huge smile, grabbed both my hands in hers, and said You have such a wonderful father!

She was smiling so hard I thought she might start crying. I nodded with as much ambiguous politeness as I could muster.

My mother showed up overdressed, overpainted, as shiny-bauble-bedecked as the Christmas tree. She addressed Edna with saccharine flattery. Oh, you are such a wonderful cook and hostess! Thank you for inviting me! Otherwise, nobody invites me anywhere anymore!

I tried not to roll my eyes in public, knowing that later on, my mother would call me to unload her real opinions, and I would sit there on the phone, immobilized, seething, yet somehow believing that it was my duty to stand by my mom against my dad. Even well into adulthood. Even knowing I would never use and abuse my own child in this manner.

Sandhya, do you see what is happening? Your father is a such different man with that woman! She really has him under her boot! Nobody likes these Filipino women, they are so demanding!

Late in the evening, I was getting ready to take my toddler up to bed when he reached his arms toward his grandmother for a hug. Somehow his own profound capacity to be warm and loving was not diminished by my mother’s fundamental falseness.

She smiled with great excitement and took him into her embrace. But then, rather than look him in the eye, rather than engage him lovingly the way he had dared to engage her, she looked out this way and that way and this way again, at all of us assembled in the room like an audience, and smiled with intense pride as if to say,

See? See? Are you all seeing this?

###

You've written such a lovely and engaging story Sandhya! As a grandmother, I read it with rapt attention to every detail of the relationships between the elders and the younger family members. It's amazing how a new baby can change our perspective and assessments of the intimate relationships shaping our lives. The fortunate among us are able to live, learn and lean in to the future with with renewed hope and purpose.